“ ‘Are we to have nothing tonight?’ said one of them, with a low laugh, as she pointed to the bag which he had thrown upon the floor, and which moved as though there were some living thing within it. For answer he nodded his head. One of the women jumped forward and opened it. If my ears did not deceive me there was a gasp and a low wail, as of a half-smothered child. The women closed round, whilst I was aghast with horror; but as I looked they disappeared, and with them the dreadful bag. There was no door near them, and they could not have passed without my noticing. They simply seemed to fade into the rays of moonlight and pass out through the window, for I could see outside the dim shadowy forms for a moment before they entirely faded away.”

—from Dracula by Bram Stoker

“Blood sucker, dream crusher, bleedin’ me dry like a damn vampire.”

—Olivia Rodrigo, Vampire (song)

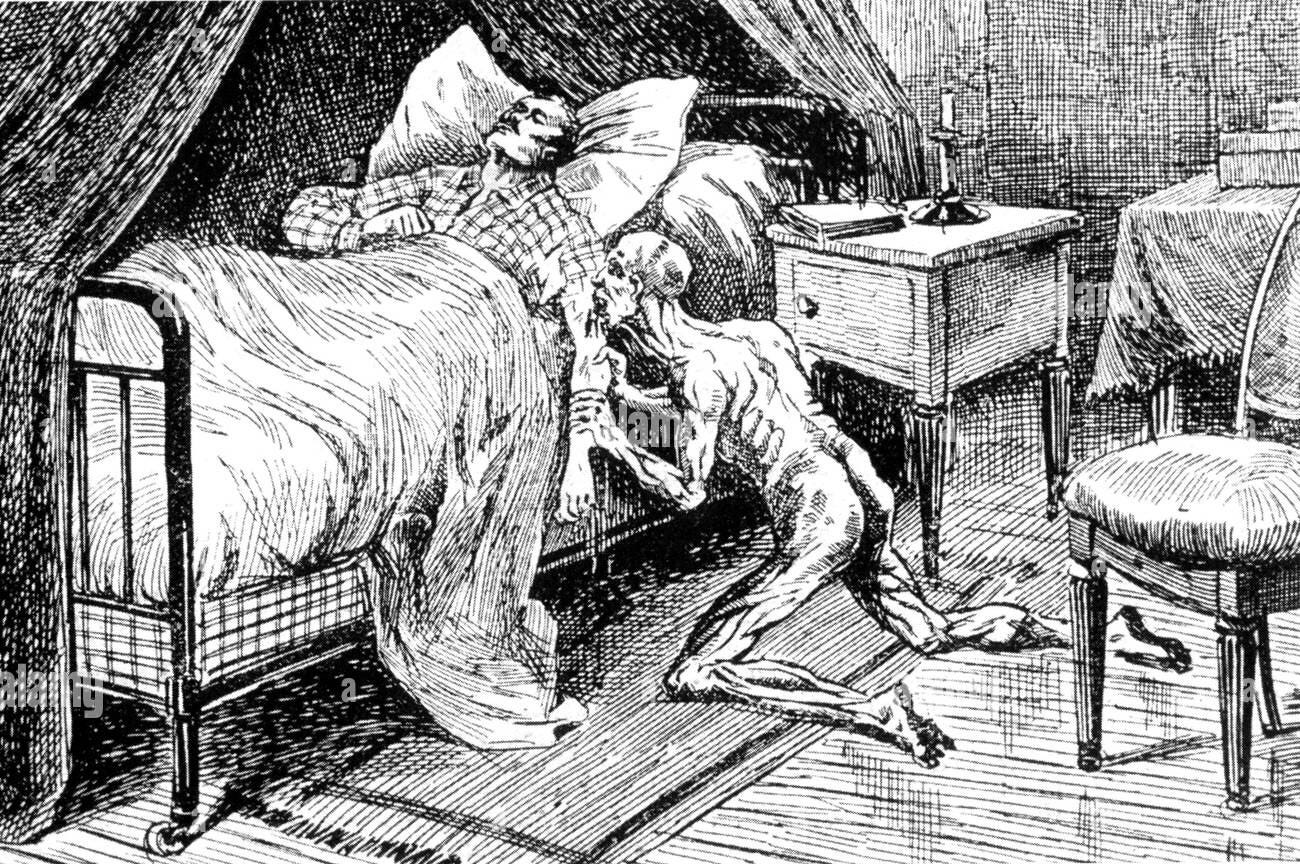

Vampires are a ubiquitous creature in popular culture. There are songs, books, films, and TV series about vampires. Every Halloween vampires flood neighbourhoods. Why do these blood drinking monsters hold such a sway over our collective consciousness? As is typical with horror, vampires fascinate and terrify, one wishes to look away, but is hypnotised by the raw brutality.

Vampires can symbolise many things: firstly, the power of blood. Blood sacrifice has figured through much of human history, as well as many other rituals involving blood, bleeding, and real or symbolic blood drinking. Christian communion is just one example of symbolic blood drinking; the wine in the chalice represents the blood of Christ. Blood is so important in myth and ritual because it is life force. Without blood, we die. Consuming the blood of another is a symbolic transference of their life force to another person or persons. Blood ritual is tied very closely to the quest for immortality, and the vampire represents both of these.

The second layer of symbology the vampire carries is a sexual one. The drinking of another’s blood is an intimate act, on the plane of a sexual act. The line between two people is taken down, and each flow into each other. In this case, the vampire’s saliva going one way, and the victim’s blood another, or in the case of a “vampire baptism” the vampire forces the victim to drink their blood while they drink the victim’s.

“The vampire bat must consume 10 times its own weight in fresh blood each day, or its own blood cells will die. Cute little vermin, ja? Blood, and the diseases of the blood such as syphilis, will concern us here. The very name ‘venereal diseases’, the ‘diseases of Venus’, imputes to them divine origin. They are involved in that sex problem about which the ethics and ideals of Christian civilization are concerned. In fact, civilization and syphilization have advanced together.”

—Van Helsing, from Bram Stoker’s Dracula, 1992

In Dracula as well as many other representations of vampires, the vampire possesses a strange sexual allure. They are free sexual beings in a repressive Victorian culture, living out their passions to the fullest. Being around a vampire excites all of one’s pent up erotic energy, and surrendering to them allows an outpouring of it. Essentially, vampires are not confined by morality, codes of decency, or accountable for their actions. They are libertines. Vampires possess the same appeal as the Marquis de Sade does. However, in today’s world where the sex act is more common, but sexual and erotic intimacy is rare, the vampire’s feeding seems very powerful and connecting. Especially since covid, physical contact with other humans is less frequent. It is no wonder that atavistic blood rituals speak to the alienated people of the digital age.

There is, however, a third layer to the symbology of the vampire. This one, in my opinion, is the most important. The vampire symbolises something economic, namely, a capitalist. Vampires are predators, as one could say that capitalists are economically exploitative. Yet in the feudal era, prior to capitalist relations, there was “actual”vampirism.

Real “Vampires” in History

There are two well known examples of “vampires” in history. One is Vlad the Impaler, the other is the Blood Countess. How much is true about these figures is hard to say, due to how myths build up, but it is interesting to note that both of these figures hail from the aristocracy. One does not often hear of peasant or working class vampires. Vlad the Impaler (Vlad III) was the prince of Wallachia in the mid 1400s. During his reign he impaled more than 20,000 people and killed thousands more. Purportedly, Vlad dined among his victims’ corpses and would dip his bread in their blood.

“I have killed peasants, men and women, old and young, who lived at Oblucitza and Novoselo, where the Danube flows into the sea... We killed 23,884 Turks, without counting those whom we burned in homes or the Turks whose heads were cut by our soldiers... Thus, your highness, you must know that I have broken the peace.”

—Vlad the Impaler, written in 1462

His reign of terror defended the Christian empire against the Ottoman empire. Some of Vlad’s violence could have come from the fact that he was held hostage by the Ottomans as a young man, but, to me, that is a somewhat flimsy excuse. Vlad’s preferred method of impaling his victims was to stick a metal pole through their rectum until it (hopefully) came out of their mouth. At times the pole would not puncture the organs, and the victims could remain alive for up to a few days.

The Blood Countess, named Elizabeth Báthory, was around from 1560-1614. Also Hungarian, she too had noble heritage. She was related to the king of Poland, the grand duke of Lithuania, and the prince of Transylvania. Apropos to her name, Countess Báthory was a serial killer. Her favourite victims were girls between the ages of 10 and 14. At first, Báthory preyed upon peasant girls, luring them in to work as maids at her castle. Two of her court officials witnessed Báthory torture and kill servant girls. Later on, she began to prey on victims of a “better” sort, namely the daughters of the lesser gentry. The girls would be sent to her castle to learn etiquette at courts, and Báthory would dispose of them. Accused of having killed between 12 and 600 girls, Báthory’s bloodlust became a legend. She tortured her victims before killing them, and some accounts say that she enjoyed drinking the blood of virgins and bathing in the blood of her victims. Needless to say, if the blood drinking of these two aristocrats actually occurred, I am sure that it was far from glamorous, and that they both probably had some very foul breath.

“As the Count leaned over me and his hands touched me, I could not repress a shudder. It may have been that his breath was rank, but a horrible feeling of nausea came over me, which, do what I would, I could not conceal.”

—from Dracula by Bram Stoker

Dracula, Then and Now

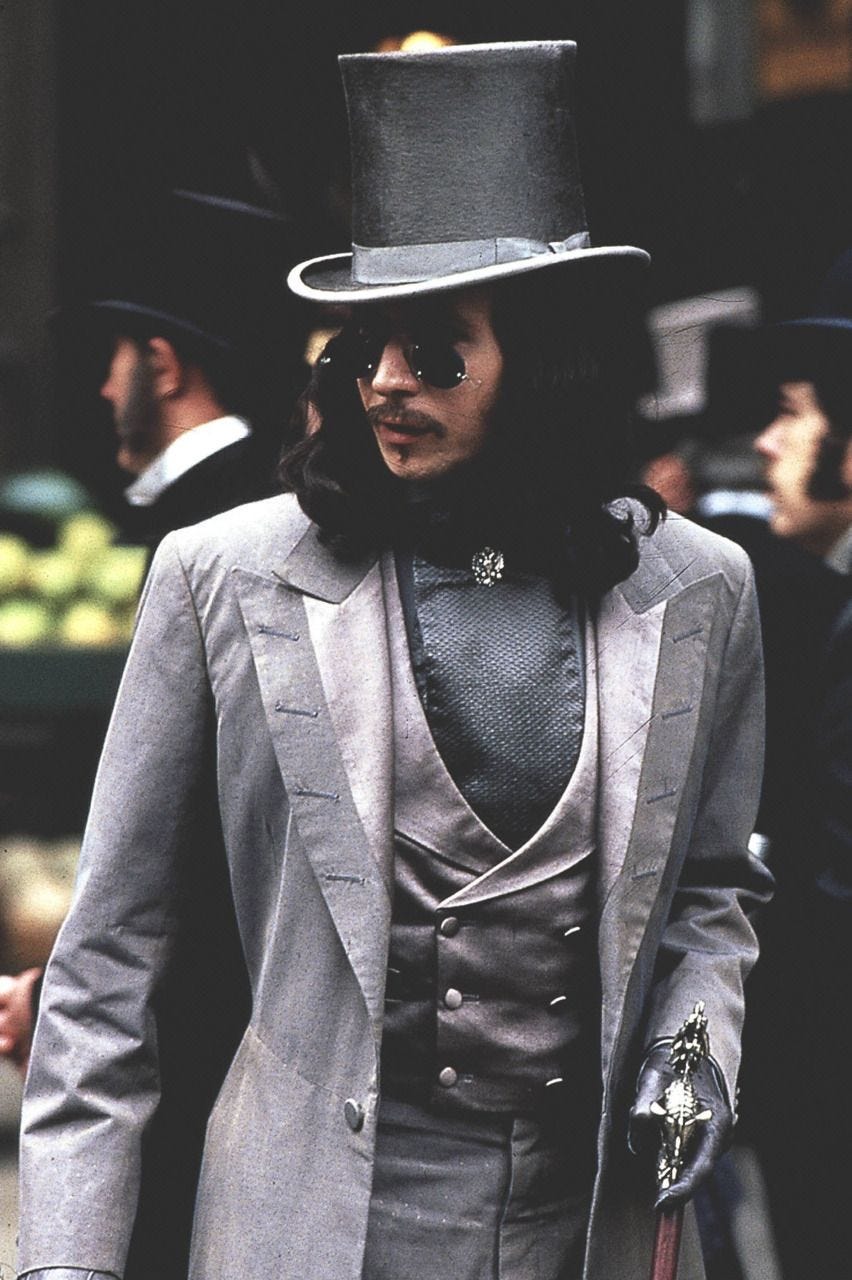

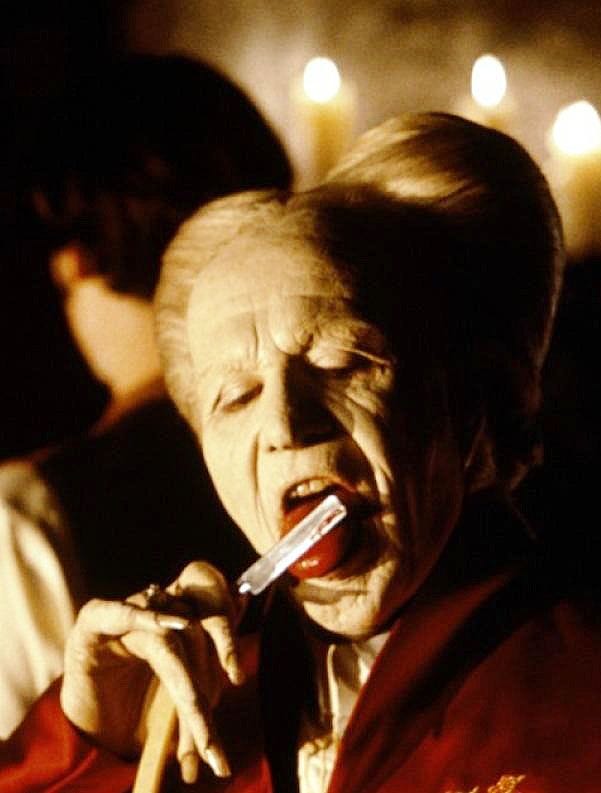

Dracula, inarguably the most well known of all fictional vampires, has changed greatly in recent media adaptations from how Bram Stoker created him. (Let me say that I did enjoy Francis Ford Coppola’s Bram Stoker’s Dracula. It is very well done.)

As Franco Moretti noted in Bram Stoker’s book Dracula is a capitalist. An investor. Dracula was buying up properties in London, shipping great boxes of earth to the properties, presumably hoping to turn all of London into a colony of vampires. Renfield, a character who is a mental patient in Dracula, constantly refers to Dracula as “master” and grovels at his feet. Suffering from extreme zoophagy, Renfield had a fascination for lives devouring other lives. He would collect flies to feed to spiders and so on up the food chain, once asking for a kitten to (most likely) eat. Eventually, Renfield ends up being murdered by the count. The count himself, Dracula, is powerful, intriguing, yet also utterly repulsive. Dracula is a perversion of all a man should be, bloated on the life force of others like a filthy leech. Bram Stoker’s intention for Dracula was to serve as a warning for real life evil.

In Francis Ford Coppola’s ‘90s film Bram Stoker’s Dracula Dracula is ultimately not repulsive, although he has his moments. The film represents the sexual dimension of the vampire very well, while ignoring the economic one. Dracula is wealthy, and does buy properties in London, but this gets drowned out in his pursuit of Minna Harker and his love for her. Coppola’s Dracula is erotic, foreign, and sexually liberates Minna and Lucy, the two human female characters in the film. In the end, this Dracula is a tragic anti-hero, he became a vampire so that his soul would dwell in hell with the soul of his beloved who committed suicide. Thus we sympathise with Dracula; he is not a monster, he is a tragedy. However, unlike many of the vampires of 21st century pop culture, he is redeemed at the end of the movie by being beheaded, thus releasing his soul from torment and ceasing to be a vampire.

Side by side, the original Dracula and the ‘90’s film Dracula are quite different. Original Dracula is portrayed in the economic dimension of the vampire, there is none of this with the later Dracula. In Coppola’s Dracula, he is sexy and alluring, albeit he is still disgusting at times in the movie. He isn’t morally repugnant like the original Dracula, he’s just sad and heartbroken, devastated by the death of his beloved. Yet this Dracula is the gateway to the modern vampires, not yet completely glamorous, yet no longer purely repulsive; sexual, yet no longer economic. Coppola’s Dracula is one of the last true vampires (disgusting at times, ultimately freed from his curse of vampirism) while simultaneously ushering in the vampire of a new age (sexy, at once tragic and glamorous, desirable). As we move forward into the age of post modern late capitalism, the powerful class message of the vampire melts away. But in it lurks a new class message… the one of the dominant class.

The 21st Century Vampire

“In a society of profit there is another truism. If something is popular, it is probably (almost, in fact, certainly) regressive and reactionary. The levers that control meaning are in the hands of the ruling class and their corporate institutions and government bureaucracies.”

—John Steppling, Already Dead

The vampires of the 21st century are glamorised, elevated to a state superior to that of humans. Being a vampire is merely a way to gain special powers, no longer does it represent utter bestiality and a renunciation of all that makes us human. In the popular Twilight series, the main character falls in love with a vampire, eventually insisting on becoming one herself. Although Edward Cullen is a “vegetarian” vampire, he is still a vampire. The vampires in Twilight have a lot money, yet where the money came from isn’t really specified. The vampires in Twilight just “have” money, which is how most wealthy people view themselves. The Twilight series effectively guts out the powerful symbolic content of the vampire myth and reduces it to teen romance absurdity. Or does it? Does this change in our cultural view of vampires, historically a monster, say something monstrous about our society?

Vampiric Meanings

To go back to the beginning for a moment, what do vampires symbolise? What are they? I will not cover their sexual undertones in this essay, but I think that it is an important element of the vampire, especially in the context of a sexually repressive society.

First of all, vampires are, in a sense, parasites feeding off of human society. They are not a part of society, rather they orbit it like planetary moons. Yet vampires draw all of their strength from human society, at once depriving it of its life force while rotting it out from the inside by transforming human beings into the undead. The vampire is a creature of the night, unable to withstand the cleansing rays of the sun, and is repulsed by all that symbolises goodness or the divine. Vampires are “lost souls”, that is why they are undead. Death is something wholesome, the decay of the flesh to energise and fertilise the new life waiting to be born. The vampire exists in a state of un-death, a reverse of death. Instead of the spirit/life force moving on as the flesh decomposes, the spirt/soul vanishes as the flesh lives on. The vampire has achieved immortality, yet it is a tortured simulacrum of life without end. Not really alive at all, in limbo, leaving no reflection in the mirror so to speak. The vampire is something chthonic, an abomination, a parasite, a predator, a rabid individualist. With its elongated canine teeth it feeds on the living while they are still alive, something that most carnivores do not do. Needless to say, I think that it should be mildly disturbing to people that these mythical creatures are held up as “cool” by many youth today. There are, however, a class of people in our society that metaphorically (and according to some deeply confused people, literally) behave in this vampiric way.

Entrepreneurial Leeches

One must either succumb to him or kill him.To return to the economic dimension of vampires, ultimately the capitalist class is vampiric. It is no accident that Marx repeatedly refers to vampires, blood, and blood sucking in Capital. For example, Marx describes capital as “dead labour, that, vampire-like, only lives by sucking living labour, and lives the more, the more labour it sucks.” In this way, by absorbing living labour, capital develops a life of its own, moving like an “animated monster”. To recap surplus labour, the worker works for a certain period of time creating a certain amount of value. A portion of this, the wage, accrues to the worker, and the rest is appropriated by the capitalist. The drive of the capitalist, as a representative of capital, is to drive the wages of the worker down and extract the greatest amount of surplus value, which is at the core of all profit. The capitalist bleeds the worker dry, so to speak. In this way, the struggle between vampires and humans becomes a metaphor for class struggle. The vampires are predators preying on humans as fodder for their life of decadence. Their drive is to enslave every being to their own dark ends, much as the bourgeoisie views the proletariat as replaceable “human resources” to be used up and discarded.

“His curse compels him to make ever more victims, just as the capitalist is compelled to accumulate. His nature forces him to struggle to be unlimited, to subjugate the whole of society. For this reason, one cannot ‘coexist’ with the vampire.”

—Franco Moretti

The fact that the economic dimension of the vampire myth has been eclipsed shows how powerful a metaphor for class struggle it can be. Instead, in popular culture the vampire myth has been turned on its head.

The Glamorisation of the Vampire

The glamorisation of vampires is a glorification of the bourgeoisie. That this has happened shows how thoroughly steeped we are in bourgeois ideology, lacking the ethical dimension to even question the correctness of vampirism. In the late 19th century, when Bram Stoker’s Dracula was written, there was enough of the pre-bourgeois morality left in society to still be repulsed by vampires. In a way people still viewed the market as a lowly place, the wealthy were dubious of overly entrepreneurial people, and society was still made up of “citizens” instead of “consumers”. The capitalist was still something crass, more reminiscent of aspiring classes than the aristocracy. Also, one cannot deny that in many ways class consciousness was running higher in the Victorian era than today.

The vampires are heroes these days exactly as figures like Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos are. Vampires are individualists at the heart of it, unfettered by community and obligations to a collective or a society. When they act as a group they act exactly as the bourgeoisie do; enforcing their class (in the vampire’s case, species?) interests, yet they are too psychopathic to truly be able to cooperate. They are inventive, wealthy, fashionable, and superior to the mass of “useless eaters” that they feed upon. The shift of the cultural view of the vampire shows the completeness of the religion of neo-liberalism. In some ways, however, it is understandable that people identify with the vampires in media (read:capitalists) because the only other option is to be the non ascendant human prey. The only other option is to be exploited instead of doing the exploiting. Yet in the internet culture of conspiracy theories (actual ones) the vampire’s economic dimension has been reappropriated in a inverted way.

Adrenochrome

Instead of viewing the bourgeoisie as figuratively sucking the blood out of a great mass of the people, there are people who view this in a literal sense. From the Q Anon theory of an underground network of imprisoned “breeders” producing adrenochrome and who knows what else for the super rich, to the notion of a blood drinking cabal of financiers, the vampire myth has been reapplied to the ruling class as reality. As much as it would be entertaining to believe these theories, in my opinion they abstract and distract from the real, material, and often mundane elements of class struggle. It is important for humans to create myth to explain reality, but myth should not be taken as reality, it should be taken merely as a means to better understand reality by using the tools of metaphor and allegory. I think that we are ruled by vampires, but just not literally. Someday I hope for a world where vampires are not admired, i. e. where capitalists are not admired. (Actually, I hope for a world where capitalists no longer exist, but that’s another story…) Where Elon Musk is no longer held up as a hero, entrepreneurship no longer a virtue, psychopathy no longer a strength. Unfortunately, this is not the case. We still exist below the vampires, or in some cases are vampires ourselves. All of us who are not members of the ruling class should remember that they are not our friends, and also remember that nothing will change if we merely aspire to their status.

“The more a dominant class is able to absorb the best people from the dominated classes, the more solid and dangerous is its rule.”

—Karl Marx, Capital Vol. 3

“I am the night

This night of space frozen by the cold idiocy of the moon.

I am money

Money that makes money without knowing why.

I am man

Man who pulls the trigger and shoots emotion

to live better.”

—Joyce Mansour

Another excellent article. I just want to emphasise that the sexual angle seems to be a necessity when “selling” vampires as entertainment. Thus e.g. “Buffy” and “True Blood”. The latter almost amounted to “vampire porn”.

One series that unwisely departed from this was “The Strain” in which the vampires were more like humanoid worms without genitalia. I don’t think it was anything like as popular as the other two.

Another very good analysis. I would add that both vampires and corporations are unconstrained by human life cycles. The live eternally across generations until someone puts a spike through their hearts.